Once a year, when the weather gets cold, a small man of

indeterminate age knocks at our door. He is not a prepossessing person. His

black watch cap is too small, his weathered blue parka is too large, he has

fewer teeth than nature intended, and he is clutching a handful of knives,

poorly concealed in a plastic bag. “Need anything sharpened?” he asks.

The first year he came I only gave him two little Opinels, in case

he decided not to come back. But he did, and now I wait for him, and I hand him all the

knives and scissors I can find, and he spirits them off for ten or fifteen

minutes, and when he brings them back they are sharper than when they were new.

His name is Jean-Baptiste, and he likes to travel. Not for

the scenery, because one village is just like another, but for the people. He

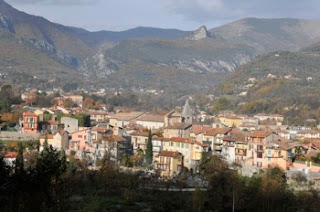

likes to talk to people. Alba is just like any other place, for example, but it

stands out in his head because the people here have a sort of a cultivated way

of talking. I ask if he enjoys that, and he says no, it is tiresome.

Toulon is where Jean-Baptiste was born and it is the place he names when asked where he’s from;

Le Teil, down the road from Alba, is where his six kids live; and if he had his

druthers he’d settle down in a town he calls Ameragues, which I have never

heard of and cannot find on any map. He assures me it is calm and restful there. He spends most of the year on the road, in a little caravan hooked to

the back of his truck. Every six months or so his truck breaks down and he plies

his trade on foot until he’s raised enough for repairs.

Toulon is where Jean-Baptiste was born and it is the place he names when asked where he’s from;

Le Teil, down the road from Alba, is where his six kids live; and if he had his

druthers he’d settle down in a town he calls Ameragues, which I have never

heard of and cannot find on any map. He assures me it is calm and restful there. He spends most of the year on the road, in a little caravan hooked to

the back of his truck. Every six months or so his truck breaks down and he plies

his trade on foot until he’s raised enough for repairs.

Sharpening knives is what he does, but poetry is what he is.

He likes poetry because it is beautiful, direct, and natural: it just comes to

him, just like that, an inexplicable gift. He doesn’t write it down – doesn’t

know how to write – but once the poetry is in his head it stays there, and he

carries it with him.

I ask him what it’s like to be a Gypsy in France today,

since Gypsies are in the news all the time over here; French policy and public

sentiment have been particularly angry and inhospitable to them in the past few years.

I ask if things have gotten harder, if he encounters any distrust or hostility, and he is very tolerant of my question and its boring lack of imagination. Lightly,

he says that there are all kinds of Gypsy, then finishes his coffee, stands up,

and leaves me with a battery of sharp knives and a poem about a rose.